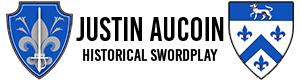

Here’s installment 2.5 of my interpretations of Francesco Alfieri‘s rapier manual. Be sure to check out the other Alfieri 1640 posts, especially the second post on the four other guards found in Alfieri’s treatise.

Today we’ll be looking at the fifth guard of single rapier found in Alfieri’s La Scherma. Yes, fifth. Along with the traditional four guards we find throughout the 17th Century Italian school, Alfieri created what he claims was a revolutionary new guard — guardia mista (“mixed guard”).

Say hello to Alfieri’s Fab Five.

Ok… but which one is Guardia Mista? Is it Jonathan Van Ness? I know nothing about Queer Eye… 😦

I wanted to give guardia mista a separate post for two reasons:

- Alfieri touts it as inventive and most of his plates & plays revolve around the guard.

- There are several interpretations of the guard and it’s worth exploring the each idea.

Of note: I’m using two translations of La Scherma. The first is translated by Piermarco Terminiello et al; the other by Tom Leoni. Both are great translators, but there is significant differences in their translations in a few spots. I did a research paper into it earlier this year. I also think reading multiple translations is a great way to get a better idea of the “spirit” of what a master is trying to communicate.

Don’t read just one book if you can help it.

Let’s jump into it.

Overview of Alfieri’s Guardia Mista

Characteristics of Alfieir’s Guardia Mista

So, what is guardia mista? It translates into “mixed guard” and Alfieri calls it his it “own invention” which has “never been devised by any until now” (easy there, Maestro Humblebrag).

Alfieri doesn’t give a great description of what the guard looks like; at least, he doesn’t give a good, useful description in our modern sense. And while I invite folks to read the two English translations out there, here are the highlights of what Alfieri does say about the guardia mista.

- The guard is used to strike the outside & inside

- It lies between terza and quarta and “shares their nature” and benefits (hence calling it “mixed guard”)

- “This consists of knowing how to adjust your sword hand and arm”

- You want to stand in a wider stance (“more wide than narrow”)

- Hold your weight is over the left leg

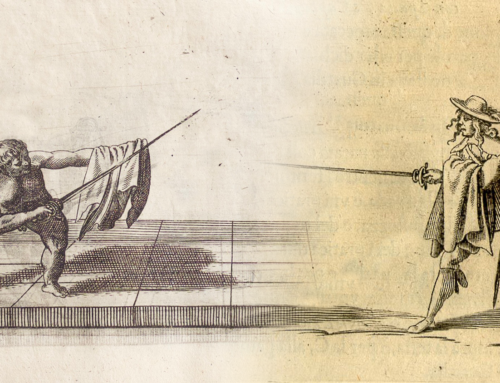

- Illustration shows the body leaned back like in a defensive terza

- Right foot is free and “quick to action”

- Sword-hand and arm are “naturally centered” (aggiustare)

- The forte and debole are both “close to where they need to be, either to defend or to wound.”

- Sword point should be aimed at the center of your opponent

- Illustration shows the point aimed at the opponent’s face

- Illustration shows the off-hand back by the left shoulder/face

- It is well adapted to form counterguards against the other four guards

Guardia Mista

Something to keep in mind when reading Alfieri, in general, is his constant call for balance and moderation. He bemoans standing or holding your posture to the extremes (standing too straight or bent too far forward), suggests not to hold your arm too extended or too refused, and warns against overextending yourself into your extreme lunge position. Similarly, he also teaches not to attack from misura stretta (which is too close to the opponent) or misura larga (which is too far) but in a measure in between the two which he calls misura perfetta (“perfect measure”). So Alfieri wanting to hold the sword also in a moderate guard (i.e., guarda mista) makes a lot of sense in terms of his teaching pedagogy.

In Book II, Chapter XXII, Alfieri alludes to talking about guardia mista in detail of Book I, Chapter I; however, this is inaccurate. Alfieri only briefly mentions his guard in Book I and it’s not in Chapter I. It does make me wonder if Alfieri meant to talk about his inventive guard in more detail and forgot — or perhaps cut it out entirely for some reason. There is definitely a lack of info of the guard in his theory section, which is odd considering how important the guard seems to be to his system as well as him touting how revolutionary it is. If he dedicated a chapter to it like he does with prima/seconda and terza/quarta, a lot of questions might be answered.

My Current Interpretation

I’ve gone through a few variations of my own interpretation of guardia mista:

- Originally I thought it was another term for bastard guard (e.g., terza-seconda or terza-quarta). This is similar to how Leoni lists the guard on ARMA.

- Then I thought it was terza held to the inside of the knee (so the hand position of terza with the arm position of quarta), which is similar to how the School of the Sword interprets the guard.

Currently, I see guardia mista as just being a more neutral terza (so the blade not angled to the outside line at all and little to no bend at the wrist). So while quarta aims a little more to your inside and terza to your outside, guardia mista is held centered between the two, so (from an overhead view; see image a little further down) a straight line is drawn from the tip of the sword to the sword-side shoulder. This is similar to the “well-formed” terza described in Vienna Anonymous (MS 381, Della Scherma) — either with or without the parting “your torso exactly in half” while standing profile.

There’s a few specifics lines that I’m mostly drawing from for this.

First, in Book I, Chapter VIII, Alfieri says mista “lies between terza and quarta.” If the angle of the sword for those guards are pointing more outside and inside, respectively, mista would fall in the middle. And we know Alfieri calls for terza to be held outside of the knee, and quarta to the inside of the knee, so having mista centered over the knee also makes some logical sense (and is a call back to the “well-formed” terza in Vienna Anonymous).

My interpretations of the relative blade position & angles of quarta, terza and guardia mista in Alfieri’s teachings. Overhead view. Hats included because it wouldn’t be Alfieri without hats.

“Terza outside the knee” is also found in Capoferro’s manual and hs interpreted by Guy Windsor and other researchers as pointing the top of the sword more to the outside line (used for stringering). We see this terza also in David & Dori Coblentz’s Introduction to Italian Rapier.

Secondly, in Book II, Chapter IV, Alfieri says that in mista, “your sword’s forte and debole are close to where they need to be, either to defend or to wound.” Also, your point is aimed at the center of the opponent’s face. This suggests that the blade is not pointing inward or outward, but straight forward without an angle to the inside or outside.

The above graphic illustrates this, too. A slight angle to the sword inward or outward means both the forte and debole aren’t “close to where they need to be” for both offense and defense.

Thirdly, Aflieri says that mista is “balanced and well adapted for forming each of the counterguards, opposing prima and seconda as well as terza and quarta.” This is pretty standard of what’s considered the well-formed terza.

This interpretation of guardia mista is pretty natural to hold and is comfortable to remain in for long periods of time, as Alfieri notes.

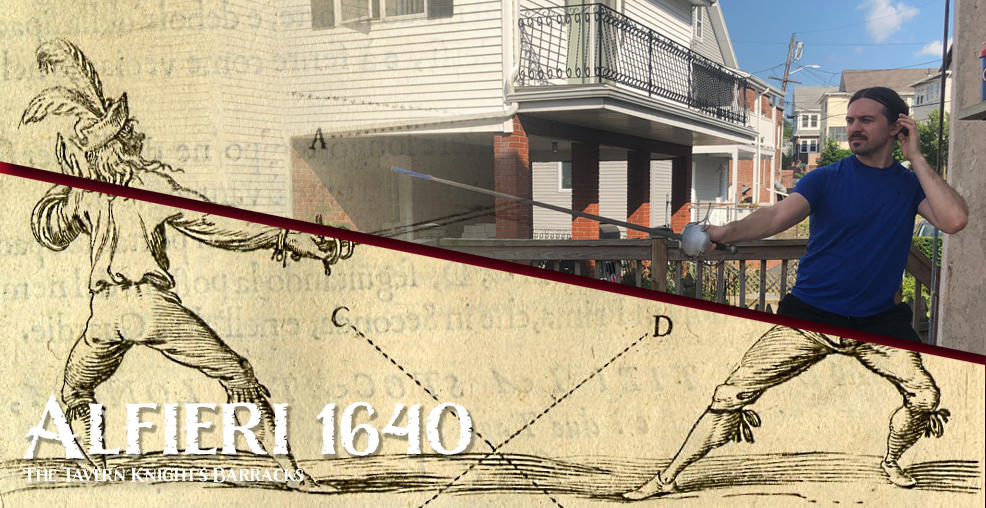

We can also grab some info from Alfieri’s plates, too. While I typically take the plates with a grain of salt, Alfieri explicitly says that “without illustrations, fencing would be grossly incomplete, since words alone cannot show the practical results of the art’s principles and remove all doubts.” So the illustrations matter in his book (to a point anyways).

If we look at the plate, we see that the hand position is in the same alignment as in terza.

Comparing the plates of Alfieri’s Terza and Guardia Mista

Both are very profiled stances with the arm gently extended at waist height. The body is inclined backwards and weight distribution is mostly on the rear leg. The off-hand is up at its shoulder or by the face. The true-edge of the sword is facing the ground and the quillons are vertical.

Here’s an overlay of the two guards. Terza is in red, guardia mista in black.

Alfieri’s terza (red) overlaid onto his guardia mista (black)

As both images show, the overall posture is almost identical. If anything, from this side view, guardia mista seems to have a slightly lower hand and angle to the wrist. At the moment, I feel more likely than not, that’s just a discrepancy in the illustration.

Unfortunately, we don’t get a front view of his guards to really confirm/deny my idea of the guard’s placement in relation to the body and we don’t get a description of it’s placement from Alfieri either.

But, if we know the hand is — more or less — in terza, it really just leaves us to figure out what about quarta is part of mista. As the next section shows, a few groups have interpreted this to mean holding terza to the inside of the knee. I’ve just taken it to mean that the sword point is neither inward nor outward, making it much quicker to both offense and defense on both the inside and outside lines. I also would hold this guard over the knee (so between quarta and terza). In all ways, it is centered, as Alfieri states.

Comparison of Terza & Guardia Mista

I’ll note that, while I’m pretty confident in this interpretation, I’m still not 100% convinced on my interpretation and am open to other thoughts. However, I think this interpretation makes sense and seems to work as intended in his plates (though I need to experiment more). In short: if you swap out guardia mista for what’s considered a well-formed terza, the actions in his plates work just fine.

In general, however, Alfieri’s description of guardia mista is too vague for my liking. Having the “nature of terza and quarta” can be interpreted in a few ways (as illustrated in the next section).

Other Interpretations:

Because of the celebrity of this guard and the vagueness in which Alfieri describes it, I wanted to also present how other practitioners, teachers, and translators have interpreted the guard over the years.

Tom Leoni

Tom Leoni is a renowned translator of fencing manuals and is a gold standard when it comes to Italian rapier translations. Leoni inserts his own ideas and interpretations of things more often in his translation of La Scherma (compared to the Terminello et al translation, which I love), including how he thinks guardia mista is formed.

In his Notes on Alfieri, His School and His Treatise, Leoni interprets guardia mista as “being formed with the quillons perfectly vertical and with the sword-arm and the sword not creating any lateral angles, i.e., located within the vertical plan bordered by the line of direction (on the ground) and the line of offense (at chest height).”

He goes on to say that he thinks the hand and sword-arm placement of guardia mista is exactly like Fabris’s “properly formed terza” (Plate 10) which calls for “justness” of the hand (hand is not turned either way). The guard gives little opening to the outside line, and, for Fabris, is the proper guard used to find the opponent’s blade on the inside or outside line.

Fabris Plate 10. The ‘Properly Formed Terza’.

This is, more or less, the same conclusion I’ve come to. The “well-formed” terza described in Vienna Anonymous refers to this “properly formed terza” in Fabris. They are the same in hand position if not in stance.

Leoni’s interpretation of guardia mista calls for a terza with no blade angle. While my current interpretation matches Leoni’s, he defends his argument slightly differently, noting that “natural terza and natural quarta (in Fabris’s parlance)” would have the sword-hand far to the right or left (respectively) to the line of offense, much like coda lunga and porta di ferro of the Bolognese system, which he says was still used during Alfieri’s time (1640).

Alfieri does, however, warn against forming these Bolognese-inspired quarta and terza guards. In Book I, Chapter XI, Alfieri notes that forming terza and quarta with the hand too low or with an angle at the hand (like we see in equivalent Marozzo guards) weakens the guard and makes performing cavaziones “useless.” Alfieri’s description of these ill-formed guards sound similar to the coda lunga and porta di ferro guards Leoni references in his notes. However, the plates for Alfieri’s terza and quarta don’t seem to match those guards — they look more akin to what we’d find in Capoferro — so I don’t think Alfieri’s terza is necessarily like this “natural terza” Leoni refers to.

Meanwhile, Leoni’s take on guardia mista is akin to what most rapier students learn as terza in modern rapier instruction, such as the Academie Duello system.

Phil Marshall

Next interpretation comes from Phil Marshall. Marshall worked on the Terminello et al translation of La Scherma and is the lead instructor at The School of the Sword in London.

He and his group released a couple of PDFs where they interpreted Alfieri’s dagger guards and cloak guards. And while the dagger/cloak versions of guardia mista are a little different than the single rapier version, we can still gleam an idea of what their single-sword version of the guard looks like from their interpretation.

Marshall and the Two’s Company interpret guardia mista similar to one of my earlier interpretations, where the sword-hand is held like terza but placed inside the knee like quarta. This does leave openings to the inside and outside line, but makes it easy to find the opponent’s on the inside and outside, too, as Alfieri notes himself.

Guardia Mista with dagger according to Two’s Company. The hand is held like terza but inside the knee, splitting the body in two.

Marshall’s interpretation also has the sword hilt held very low, basically at groin height with the blade at an extreme angle toward the opponent’s throat. This, however, doesn’t really match up with how Alfieri describes the guard or how the plates show guardia mista. Specifically, Marshall’s interpretation of the dagger and cloaked guards appear to be too low compared to Alfieri’s plates, and seem more akin to what we’d find in Marozzo‘s Bolognese sidesword system. It may be important to note that Alfieri does refer to Marozzo in La Scherma, albeit unfavorably (Book II, Chapter XX).

Guardia Mista with cloak, according to Two’s Company. In this version, the hand is turned closer to a terza-quarta position.

Alfred Hutton

Guardia mista is also referenced by Alfred Hutton in his book on sabre fencing, Cold Steel. In it, he says, “Of these the Tierce, and especially the Medium, which is nothing more than the ‘Guardia Mista’ of Alfieri (1640), are the best for the combined purposes of defense and attack, because in these positions the arm is least likely to become fatigued, and it is on this Medium Guard that I shall, following the advice of practical old Alfieri, base all my ensuing lessons.”

Hutton says his Medium Guard is the same as Alfieri’s Guardia Mista

Hutton also said that the “Medium is neither Quarte nor Tierce, but, as its name suggests, is immediately between the two, the edge being inclined downwards, and the point opposite to the opponent’s face.”

Not sure if Hutton meant this, but connecting his Medium Guard to Alfieri’s guardia mista plays well into Alfieri’s ideal of balance/moderation/medium that I discussed earlier.

I.M. Davis

Our fourth interpretation comes from a translation by I.M. Davis and uploaded to Scribed by Janish Cruel. This is a short 27-page interpretation of some plays and concepts found in La Scherma. It’s not a strict translation like in the Leoni and Terminiello version, but a short summary of different plays. I’m unfamiliar with I.M. Davis and was unable to find any other of their work or context for who they are (if you do know, though, please leave some comments below!).

Davis’s interpretation of guardia mista also calls for the guard to be held “halfway between terza and quarta” but adds that the body should be positioned like in terza with the sword held “somewhat closer to quarta” with the palm of the sword hand facing somewhat to the right and up (so, similar to a bastard terza-quarta found in Giganti). This is pretty similar to the Marshall/Two’s Company interpretation of the guard.

I’ll also note that during my read through of the paper, the author seems to take some liberties with the plays described in Alfieri’s Book II chapters, such as changing the guards explicitly used, the line in which an attack is done, and the general actions the fencers to take.

Where Does This Leave Us?

Alfieri Plate 4. His Guarda Mista (“mixed guard”)

In the end, guardia mista is still a bit of an enigma. At best, it puts more emphasis on the “properly formed terza” and not an angled version of the guard; at worst, it’s a terza that Alfieri slaps with a superfluous name and uses as a point of differentiation in the mid-17th Century fencing market. Marketing, baby.

My interpretation of guardia mista being a “well-formed” terza did mean I had to reevaluate how Alfieri’s regular terza looks, hence why I have that guard with a slight angle to the wielder’s outside line.

In the end, I think practitioners looking to practices a very Alfieri-centric style of Italian rapier can get away with substituting guardia mista for terza and it’s bastard mutations when finding an opponent’s blade.

How do you interpret guardia mista and why? Leave your thoughts in the comments below!

Next up, we’ll look at Alfieri’s dagger guards.

DONATIONS: If you found this video & blog useful, please consider a small donation so I can continue to produce rapier & other historical martial arts content. Donate at https://www.paypal.me/BostonAcademiedArmes. Or hire me for your next event or workshop!

Sources:

Alfieri, Francesco Ferdinando. La Scherma: The Art of Fencing. Padua, 1640. Translated and edited by Caroline Stewart, Phil Marshall, and Piermarco Terminiello. Fox Spirit Books, 2017.

Alfieri, Francesco Ferdinando. La Scherma: on Fencing, 1640 Rapier Treatise. Padua, 1640. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Self-published: Lulu, 2018.

Boorman, Devon. Introduction to the Italian Rapier. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2017.

Capoferro, Ridolfo. Ridolfo Capoferro’s The Art and Practice of Fencing: a Practical Translation for the Modern Swordsman. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2011.

Coblentz, David and Dori, Introduction to Italian Rapier. Accessed on July 13, 2020. http://www.thecoblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Italian-Rapier.pdf

Davis, I.M. Rapier Fencing of Francesco Alfieri. Scribd.com. Accessed on July 10, 2020. https://www.scribd.com/document/334183992/Rapier-Fencing-of-Francesco-Alfieri

Fabris, Salvator. Scienza d’Arme (The Art of the Italian Rapier). Copenhagen, 1606. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005.

“Francesco Fernando Alfieri.” Wiktenaur. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.wiktenauer.com/wiki/Francesco_Fernando_Alfieri

Hutton, Alfred. Cold Steel: The Art of Fencing with the Sabre. London, 1889. Republished New York. Dover Publications, Inc., 2006.

Giganti, Nicoletto, Venetian Rapier: The School, or Salle. Siena, 1606. Translated by Leoni. Freelance Academy Press, Inc., 2010.

Leoni, Tom. “A Brief Glossary of Italian Rapier Concepts”. ARMA. Accessed July 13, 2020. http://www.thearma.org/rapierglossary.htm

Marshall, Phil. “An introduction to the use of the cloak in Italian rapier play.” Two’s Company at The School of the Sword, 2007. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://sword.school/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Twos-Company-PartII.pdf

Marshall, Phil. “An introduction to the use of the dagger in Italian rapier according to Francesco Alfieri.” Two’s Company at The School of the Sword, 2007. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://sword.school/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Twos-Company-PartI.pdf

“The Guards.” Marozzo.org. Accessed July 13, 2020. http://www.marozzo.org/marozzo/bolognese-guards.htm

Vienna Anonymous on Fencing: A Rapier Masterclass from the 17th Century. Based on Fabris & Capoferro. Transcribed, translated, annotated, and edited by Tom Leoni. Self-published: Lulu, 2019.

Windsor, Guy. The Duellist’s Companion. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2006.