It’s Cloaktober! This month marks the third year of celebrating the use of the cloak with the rapier. While the Boston Academie d’Armes group class is focusing on Fabris’s cloak, I wanted to do a post on how another Italian fencing master approached the cape — Francesco Alfieri.

As always, I see interpretations of living documents that can change over time with new info and insight. I’m always happy to hear about folk’s own interpretations and the like.

To get going, we’ll look at the various guards/postures with cloak, as described by Alfieri. I get into a little detail, but if you want the tl;dr version, you can watch this video or jump to the last section of this blog.

Quick History Lesson

Alfieri’s cloak chapters make up the final section of his book, but as he notes, “We should take even more care to familiarize ourselves with the cape than with the dagger, which is not everywhere permitted, while the cape has never been denied to those who have the ability to use it.”

In short, according to the footnotes in Piermarco Terminiello et al‘s translation, some cities and Italian states outlawed carrying various classes of weapons, such as thin-bladed daggers like the stiletto and other dagger types considered to be “assassin weapons” such as sfondagiaco, quadrello, and the verduco. A general ban on common, everyday daggers were more rare but did happen on occasion.

Regardless, no city or nation state in the 17th Century was banning cloaks or capes, meaning it was always a viable offhand secondary. The use of the cloak and coat in self-defense carried through the age of the rapier into the smallsword, and is still a viable offhand secondary in modern knife fighting and self-defense.

Still, the cloak is an often misunderstood and underutilized companion to the rapier. In the SCA, the cloak is used like a twirling pendulum, more likely to get in the wielders way than the opponent’s; in HEMA, it’s mostly forgotten or a mere novelty.

Alfieri’s Rapier & Cloak Guards – Plate 33

Source: Wiktenaur

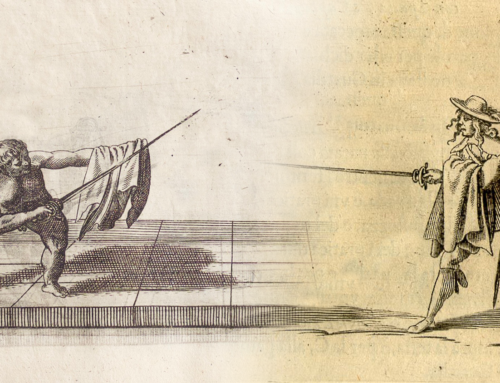

Alfieri’s Plate 33, showing terza with the cloak (left, figure 60) across from guardia mista with the cloak (right, figure 61). Additionally:

- Line A shows the rough location of the sword for prima.

- Line B is a high version of guardia mista as a contrapostura (counter-posture).

- Line C is the rough angle of the sword for quarta with the cloak.

- Line D is the rough angle of the sword for a low version of guardia mista.

Seconda is not explicitly or implicitly shown on this image but is described a bit in the accompanying text.

For this post, I’m working off of two translations:

- The first is translated and edited by Caroline Stewart, Phil Marshall, and Piermarco Terminiello in 2017 (we’ll call it Terminiello et al for shorter reference)

- The second is translated by Tom Leoni in 2018

Links to these books in the sources section at the end of the post.

Prima

Let’s start with the first guard, prima.

The translation for Alfieri’s cloak prima is similar between Leoni and Terminiello et al.’s translation.

The prima with the sword and cape does not change its nature as far as the placement of the body, feet, arm and sword. Fencer 60 must lift his arm to line A, keeping the left arm well extended with the cape around it.

The sword is held at/above head height, sword-arm withdrawn and cloak extended forward. This is similar to how Alfieri approaches prima with the dagger, which he notes is good for defense but not offense.

Seconda

Next up is seconda which may be formed differently, depending on which translation you’re reading.

From Leoni’s translation:

The seconda is formed by lowering the arm to shoulder-height.

The Terminiello et al translation reads:

Seconda is formed by lowering the arm in a straight line from the shoulder.

In Leoni’s translation, seconda with cloak looks like prima with cloak, but the arm and hand held at shoulder height. However, in the Terminiello et al translation, it seems that not only is the sword arm/hand held at shoulder height but the hand, arm & sword is held fully extended toward the opponent, creating a straight line from shoulder joint to sword tip. This difference in translation isn’t an isolated incident, as I’ve explored in other Alfieri projects; there are several chapters in which the translation between Leoni and Terminiello et al. vary greatly enough to alter interpretation of the plays. This seconda with the cloak is no different.

For context, the original Italian reads:

La Seconda si forma con abbassar il braccio à drittura della spalla.

…which Google translates to “The second is formed by lowering the arm straight to the shoulder,” so it’s easy to see where both translations come from. Alfieri’s ambivalent word-use is a common issue in his treatise; he also tends to leave useful details out of his plays. Anyways…

Both have merit as being correct.

As a guard or starting posture, Leoni’s version falls in line with how Fabris shows seconda with the cloak. It also falls in line with what we see in Alfieri’s other cloak guards of prima, terza and quarta — the sword is withdrawn and the cloak extended. Terminiello et al‘s translation, however, reads similar to how Alfieri approaches seconda with the dagger — sword extended and secondary covering the low line under the hilt. It’s also a good final alignment of sword and cloak after lunging in seconda.

Lunging in “closed-seconda”

So even if we defer to Leoni’s translation, Terminiello’s should be noted. It’s martially sound.

Alfieri makes no mention on where the cloak should be in this guard, so assumptions need to be made. If you think the cloak is extended like in prima, then Leoni’s version is probably the best best; if you don’t assume that, Terminello et al version works best.

I lean toward the Leoni version in this case, but that could be some Fabris-bias showing.

Terza

Unlike seconda, terza is pretty straight forward thanks to being one of the two illustrated guards. Alfieri writes:

For the terza, the hand needs to be lower, close to the thigh, as we see in the position of fencer 60.

This posture is falls in line with Fabris’s basic terza with the cloak, though Fabris shows the cloak arm a smidge more withdrawn and with a gentle bend at the elbow. It’s hard to know how spot-on the drawing is to what Alfieri actually wants.

Quarta

Next we have quarta:

The quarta originates by placing the arm on line C, with the sword-point aimed to the ground and the cape-arm extended.

There’s no mentioning if the sword is extended or withdrawn, though we can assume withdrawn since the cloak is extended — which is common practice in the Italian system. The sword point being aimed toward the ground is unique. In fact, having a quarta guard for cloak is unique among the “Big Four.” For example, Fabris doesn’t show a quarta with cloak, and Capoferro and Giganti just show terza and terza-variants. So we don’t have a lot to work off of from outside but related sources. We can see what Alfieri says about quarta in his dagger section for additional clues:

If you place the sword along line A, however, this becomes quarta, which to be faultless requires the hand to be inside the knee, with the arm extended so it forms a straight line from the elbow to the point of the sword, the dagger remaining straight and close to your hilt.

It appears that his quarta with dagger is different enough from cloak, however. In dagger, the dagger is near the hilt of the sword but in cloak, the cloak is extended (held further out from the body). Although Fabris doesn’t have a cloaked-quarta, he does have something similar in his dagger section, which shows the sword point held low and partially extended.

In my interpretation, Alfieri’s quarta with the cloak is still extended like we see in prima, seconda (Leoni translation), and terza. The hilt of the sword is a little further forward than terza, mostly because our body is in the way if we were to bring the hilt directly across from that guard. The hilt is mostly hidden by the leading edge of the cloak and is held near(ish) to the cloaked hand, so there’s no gaps between sword and cape. The tip is held low, beneath our opponent’s hilt at minimum, making it difficult for them to engage our blade.

Alfieri’s plays with the cloak never mention quarta, so we never get a practical look at how he wants to use this guard, sadly.

Guardia Mista

You can make the argument that my sword should be further inside the knee, but like with all guards, there’s wiggle room.

Alfieri’s mysterious fifth guard which has has modern rapier practitioners debating what exactly it is. I did a long post on guardia mista , but the tl;dr version is you can swap it out for a standard terza and it changes nothing about how plays or actions work. It’s just a terza variant.

In this case, guardia mista is a sword-extended/cloak-withdrawn terza with the cloak held close to the hilt of the sword in what we call the “closed-position” since there’s no gap between the sword and the cloak. The body is held in a normal Defensive Posture/Common Italian Stance with the torso reclined over the rear hip and the sword extended or slightly hinged forward in the Forward Guard/Offensive Posture. This is similar to how Giganti and Capoferro approach cloak, as well as Fabris’s cloak posture for when your cloak-shoulder gets tired.

It’s of important of note that Phil Marshall, one of the other folks in the Terminiello et al translation, interprets this guard with a bit more of an extreme angle of the guard and the hilt well inside the knee.

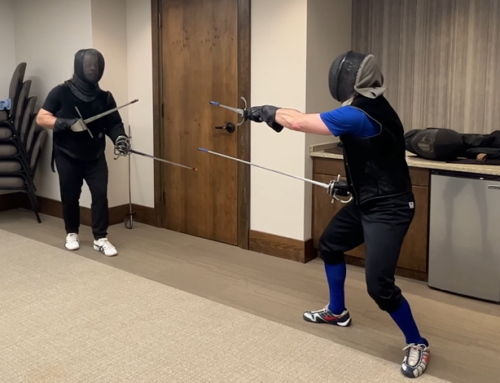

Guardia Mista with cloak, according to Two’s Company. In this interpretation, the cloak is held much higher than the sword hilt, the angle of the blade is steeper, and the sword is further inside the lead knee.

Alfieri also lists two alternative, counter-postures for guardia mista, which has the sword held high or low, but doesn’t get into more details than that.

The low version of guardia mista would look pretty similar to Capoferro’s quinta or what other Italian masters would describe as a low-terza.

The high version most likely would be to counter swords held higher, like in the Spanish destreza or someone in a guardia alta position.

In general, I think the dotted lines are more like guidelines and not to be taken 100% literal.

Creating Various Invitations with Cloak

Alfieri doesn’t get into depth about what lines these postures cover and what the invitations are, so this section is a bit off script if we care only about what Alfieri thinks. But as modern practioners who study the art, it’s still a concept worth thinking about. For each of these guards there’s a “natural” invitation and then one we can create or manipulate by moving our bodies a little bit.

For example, in prima with the cloak, the natural invitation is under the sword to the low-outside line (the extended cloak covers all of the inside line). However, if we rotate our torso and bring the sword and cloak toward our sword-side, we close off the outside line and create a single invitation over the cape to our face (high inside line).

Seconda works similar to prima. The natural invitation is under the sword to the low-outside line (assuming the Leoni version). If we bring our shoulders and hips toward our sword-side, that invitation becomes over the cloak to our face.

Terza isn’t too dissimilar. The natural invitation this time is over the sword to the high-outside line toward our sword-side chest. If we bring cape & sword to our outside line, that creates a singular invitation over the cloak to our face.

Quarta is an odd duck, but works on the same principles. The natural invitation is over the sword to the high-outside line but if we shift everything to the outside line, we create that invitation over the cape. The blade being more extended means someone may try to engage the blade on the low inside- or outside-line.

Corporate wants you to find the difference between these two photos.

Guardia Mista works like terza in single rapier. The invitations are driven really by the sword alone and what lines we’re constraining, etc. If we find/gain on the outside, the invitation becomes to our inside line and vice versa. With that said, in Alfieri’s dagger section, he mentions that guardia mista has “its opening to the outside” so we can assume similar works with cloak. He also talks about creating an invitation over the cape in his first cloak play.

In general, the cloak naturally negates targets on our inside line, leaving the outside line as the main line of attack to worry about. This is especially true in our cloak-extended guards which better utilizes the cone of defense and the sheer length/volume of the cloak. It’s a lot of zone defense. But we can manipulate the invitation we offer by how we hold our body and weapons. If we know that our opponent loves head shots, for example, manipulating our posture so our head/face is the invitation might be a good strategy.

Regardless, best practice with the cloak is to create a single invitation, so our opponent only has one option for a straight attack, thus making our defensive response simple and quicker.

Summary of Alfieri’s Rapier & Cloak Guards

Here’s the tl;dr version of what I think Alfieri’s rapier and cloak guards look like.

[/fusion_text]

DONATIONS: If you found this video & blog useful, please consider a small donation so I can continue to produce rapier & other historical martial arts content. Donate at https://www.paypal.me/BostonAcademiedArmes. Or hire me for your next event or workshop!

SOURCES

Alfieri, Francesco Ferdinando. La Scherma: The Art of Fencing. Padua, 1640. Translated and edited by Caroline Stewart, Phil Marshall, and Piermarco Terminiello. Fox Spirit Books, 2017.

Alfieri, Francesco Ferdinando. La Scherma: on Fencing, 1640 Rapier Treatise. Padua, 1640. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Self-published: Lulu, 2018.

Capoferro, Ridolfo. Ridolfo Capoferro’s The Art and Practice of Fencing: a Practical Translation for the Modern Swordsman. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2011.

Fabris, Salvator. Scienza d’Arme (The Art of the Italian Rapier). Copenhagen, 1606. Translated and edited by Tom Leoni. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005.

Giganti, Nicoletto, The ‘Lost’ Second Book of Nicoletto Giganti (1608). Siena, 1606. Translated by Piermarco Terminiello and Joshua Pendragon. Fox Spirit Books, 2013.

Wiktenaur, “Francesco Fernando Alfieri.” Transcription by Andrea Conti. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Francesco_Fernando_Alfieri

IMAGE CREDITS

Fabris & Capoferro images compliments of Guy Windsor.

Alfieri plate images from Wiktenaur.