About a year or so back, while I was reading through both the Leoni and Terminiello et al translations of La Scherma, I noticed several chapters where the translations differed a lot. Not just synonymous word choice variations between the two translations, but sufficient differences that greatly altered martial interpretation.

I found this fascinating. I wondered: if two students read a different translation and then came together to practice it with one another, just how big of a difference would it be? What would one learn that the other didn’t? Would the plays even be recognizable as coming from the same chapter?

This was the basis of my research paper for East Kingdom Crown A&S. I wanted to explore what these translation differences were and how it would affect a modern fencing practitioner’s interpretation of the play.

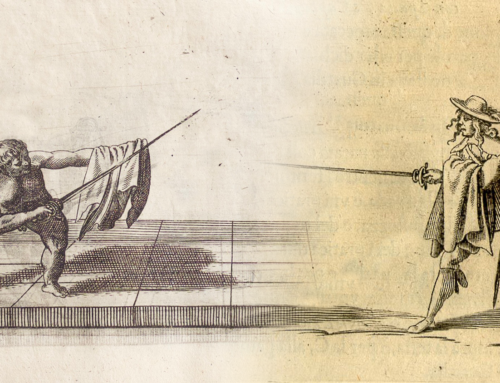

I focused on one chapter in particular — Book II, Chapter VIII, entitled “On Wounding to the Outside Over the Sword, Passing with the Left Foot” — because it had numerous translation differences (four, in total) as well as impactful differences that really altered how someone would learn the chapter and the tactics involved.

I also wanted to see how the two translations compared to other 17th Century Italian fencing masters; however, this was more to connect it to the pre-1600 SCA-era than anything else (Alfieri’s La Scherma came out in 1640).

I presented my original findings for the Martial A&S competition at St. Eligius and then did a follow-up blog post with another fencer’s thoughts on the matter. These two posts may also be of interest to readers.

Download! Get Yer Download Here!

You can download a PDF version of my paper right here. Enjoy.

Feel free to leave comments below or email me.

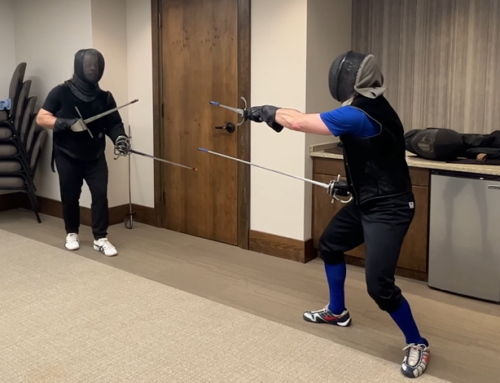

Display Video

Below is the video I played on loop at Crown A&S. It’s a Cliffnotes version of my paper and main goal was to get the major ideas across quickly and in visual way to a mostly non-fencing audience.

More detailed videos (profile as well as 3/4 angle shots) are embedded in the body of the research paper, are listed in the appendix, and can be found on my Youtube page.

Notes:

- For this web version of my paper, I have embedded links directly to all the books, videos, and blog posts in the body of the paper, so readers don’t need to skip back and forth to the appendix.

- One of the questions brought up by the judges was the qualifications of the translators. This info was in my original paper but I took it out in the final draft. I have added it back into the paper in the appendix.

- Another question from the judges was why are the translations different. I have my theories and provided them to the judges when asked, but I felt like that was outside the scope of this paper. I was more concerned about how translation differences affect martial interpretation more than why it happened. I do find the why fascinating and hope to do a follow-up blog post at a future date. Stay tuned.

- A critique from the judges was that I didn’t take a strong enough stance on which interpretation was “more right” (my words) than the other. This was part of my original paper but, after feedback test readers, I felt like to do it properly would’ve turned the project into a linguistics paper (which isn’t something I wanted to cover). In hindsight, I could’ve approached it from a martial tactics angle and not linguistics. I’m hoping to maybe add my thoughts on this in a future blog post on why things were different.

- Regarding the videos: My measure is closer than I normally would be in combat. I did this to simulate my blade running through my opponent, as shown in the plate. Alfieri calls for the sword length to be as long as the floor to your armpit, which is several inches longer than I use. When performing these plays at speed in an SCA/HEMA/WMA sparring setting, I would bring my measure back for safety reasons.

- A second note on the videos: Alfieri says to use the third of the blade closest to the debole for cutting. In some of my videos I use near the bottom of that debole third, but sometimes I’m a little too close to the mezza spada. I had just gotten over two weeks of the flu and had to cram all filming into one session, while also playing producer and cameraman, so forgive the sloppiness in that technique.

As always, I’m open to others thoughts on this topic. I find the translation differences fascinating, especially how it affects how a student would interpret and learn the chapter.

I’d love to hear other practitioners’ experiences in this area and how they interpret the plays. Also curious as to which translations might be “more right” than the other. I have my own thoughts on the matter.

Thanks again to my test readers, proofreader, judges, and everyone who swung by my table during the day. Enjoy!

Or, you could translate the Italian, instead of taking the translations as handed down from on high like Jerome’s Vulgate. The problem is that Alfieri’s own language is ambiguous, and as translators Tom and Pim had to make sense of it. Here is a rendering of it with all the confusion preserved:

Finding the gentleman (14) in fourth, the person who strikes (15) goes resolutely to engage his enemy’s weak with his strong; who tries to disengage, and to forestall this with a thrust, and be wounded in second, and goes forward on the outside over the sword with the left foot in the same moment [“moment indivisible”] with the disengagement.

Without getting into too much detail, this has a lot of problems from a technical standpoint, and, while we can make this into a logical sequence by adding elements, we need not think Alfieri’s texts, as received, is flawless.

Sadly, I don’t know Italian so, like many others, I have little choice but to take the translations of those who do. I could run it through Google Translate but that’s fraught with it’s own issues.

I agree that Alfieri’s writing is pretty ambiguous. It’s probably my biggest complaint about his manual. There’s also a lot of gaps and details he leaves out.

Also it’s outside the scope of my paper.

The trouble is Alfieri’s use of punctuation, which leaves room for ambiguity, particularly where it’s not clear how one clause relates to those around it. A very literal translation, with the original punctuation would be:

Finding himself the gentleman 14. In quarta the wounder 15. He has gone resolutely to bind with the strong the weak of the enemy, who wishing to disengage, and beat him to the strike, is wounded in seconda, and to the outside, over the sword carried forward with the left foot in the indivisible moment of the disengage.

He can also feint, and wound at line B, in second under the right arm to the flank, and finally, beat the sword to the outside, but with reason since he does not have time to disengage, and from point A, unleash a mandritto, or riverso tondo to the head.

Yep. Totally agree. The poor punctuation and the word “finally” are the two main reasons why I think we have two varying translations of this play.

Thanks for the comment and your translation!