NOTE: Since posting this blog yesterday, I’ve had some great convos with other historical fencing practitioners and it appears that I may be interpreting part of the play incorrectly (mainly the starting line which Alfieri doesn’t mention). I’ll be reevaluating my thoughts based on that, but I’m leaving this blog post up just the same, as trial & error is part of the process.

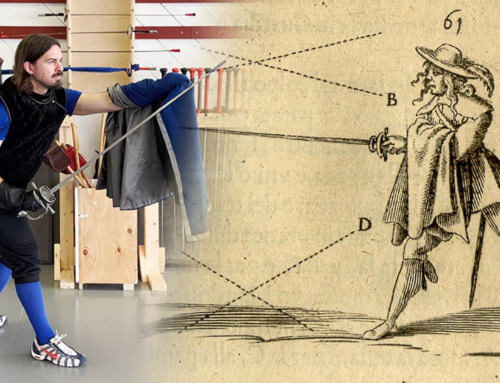

Yesterday was the St. Eligius event, an A&S-centric event in the East Kingdom. Along with the main A&S competition displays, there was a Martial Combat A&S Challenge. The goal of this was to choose a plate from a period fencing master, document it, and present the plate’s action(s) for a team of judges.

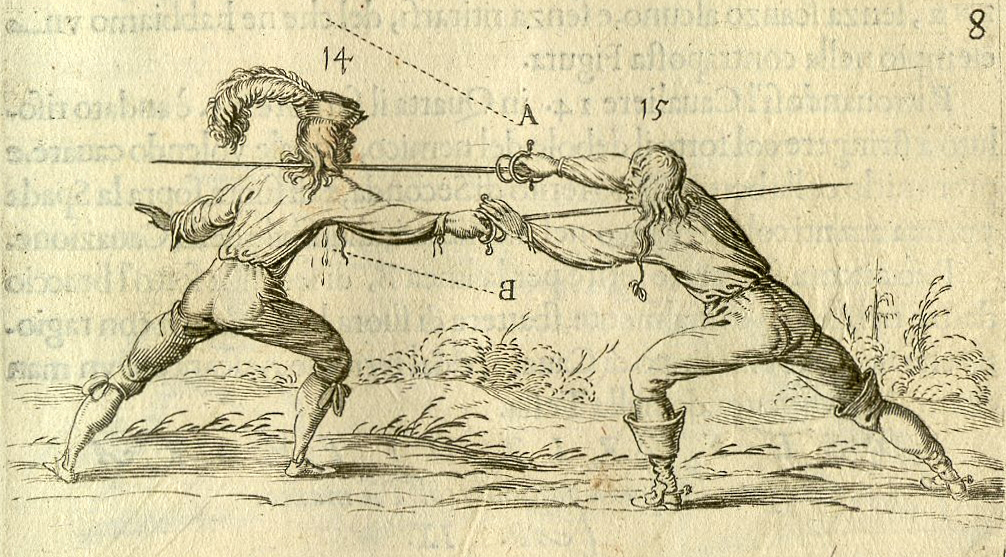

I decided to demonstrate and present Book II, Chapter VIII of Alfieri’s La Scherma. I demonstrated two translations of the chapter — one by Tom Leoni and the other by Piermarco Terminiello.

The translation between the Leoni and Terminiello versions vary enough in the second half of the chapter that it greatly alters the martial interpretation of the chapter. This means you could have two fencers learning very different plays depending on the translation they’re learning off of.

EDIT: It’s been asked that I put the two translations in the body text so it’s easier to read for folks on mobile who may not be able to download the PDF handout. I’ve bolded the sections where the translations differ:

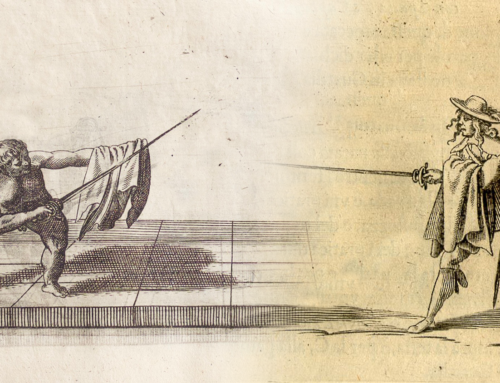

Leoni Translation: “Fix-footed attacks are very common and quite safe in duels. I recommend practicing this type of strike to develop agility in your foot, as well as to make your lunge longer than a natural motion. Passing, however, is also not to be overlooked. By doing so, you unsettle the opponent and throw him into disorder, and you proceed with more momentum. Passing attacks must follow a straight line all the way to the opponent’s body, without any lateral voiding and without pulling back. This illustration gives an example of such attack.

The opponent (14) is in quarta, and you (15) take the initiative and gain his debole with your forte. He attempts to beat you with a cavazione but is defeated by your thrust in seconda to the outside line, above his sword and carried by your left foot in the indivisible motion of his cavazione.

You could also feint in seconda along line B (to the flank under his right arm), beat his sword to the outside (making sure he doesn’t have the time for a cavazione) and deliver a mandritto or riverso tondo to his head from line A.”

Terminiello Translation: “Attacking from a firm foot is very common and is extremely secure. I praise practicing this blow in order to acquire agility in the foot and to extend the thrust beyond its natural motion. Passes are not to be disparaged as they disturb and disorder the enemy and they travel with greater force, bearing in mind that you should carry on passing in a straight line until you reach your opponent’s body, without stepping offline and without retreating, which we have an example of in the figure opposite.

Turning to Gentleman 14, the wounder (Gentleman 15 in quarta) has moved with resolution to bind the enemy’s debole with his forte. Gentleman 15 wishes to perform a cavazione and beat his opponent to the blow but is wounded to the outside above the sword by a seconda, carried forward by a left foot pass during the midpoint of the cavazione.

Gentleman 15 could also feint, and wound along line B in seconda, to the flank under the right arm.

Finally, he could knock the sword to the outside, with reason as he does not have time to perform a cavazione, and from point A deliver a mandritto or riverso tondo to the head.”

You can download my presentation handout here.

Things not covered in the handout that I went over in my demo/presentation were reasons why I think the Leoni version is problematic. This included:

- Giving up control of your opponent’s sword — as is basically described in the Leoni translation — is not a wise move and doesn’t fit in the greater Italian school mindset. This makes it easier for your opponent to now dominate your own sword and put you at a highly disadvantageous position.

- Feinting low, below your opponent’s sword while in measure — as described in the Leoni translation — opens your entire high line and makes for an easy attack by your opponent to your upper torso and face. There’s little defensive options should your opponent not buy the feint and instead attack.

- Feinting and blade beats are both actions used to create tempos to attack. To feint and then blade beat as your next action is creating a tempo to create a tempo and is overly complicated. It’s not demonstrated anywhere else in Alfieri and related masters. The double-feint doesn’t really become “a thing” until the smallsword and even masters of the smallsword discouraged the action.

There are two other chapters in Alfieri where we find other translation differences that greatly change the martial interpretation of the plays at hand. This translation phenomenon is the focus of a larger paper that I’m hoping I’ll debut at K&Q A&S next spring, so this presentation was kinda a test-run of the idea.

Seems people found it as fascinating as I did, as I won the Martial Combat A&S Challenge. Got a sweet book for a prize and a couple of tokens. This was my first time entering an A&S competition, so I’m more than pleased with the results.

The moral of the story is to always cross-references as many sources and translations as you feasibly can for the best understanding of the system you’re studying.

Special shoutout to Grímólfr Skúlason for being my “pin cushion” for the presentation.

Photos by Samantha Raven/Sitt al-Gharb ha-nigret Khazariyya.

[…] So a couple of month’s back, I did a presentation on two translations of Chapter VIII of Alfieri’s La Scherma and then posted my notes/thoughts in a blog post here. […]